Ficus

|

Moraceae > |

Ficus > |

Ficus (pronounced /ˈfaɪkəs/)[1] is a genus of about 850 species of woody trees, shrubs, vines, epiphytes, and hemiepiphyte in the family Moraceae. Collectively known as fig trees or figs, they are native throughout the tropics with a few species extending into the semi-warm temperate zone. The so-called Common Fig (F. carica) is a temperate species from the Middle East and eastern Europe (mostly Ukraine), which has been widely cultivated from ancient times for its fruit, also referred to as figs. The fruit of most other species are also edible though they are usually of only local economic importance or eaten as bushfood. However, they are extremely important food resources for wildlife. Figs are also of paramount cultural importance throughout the tropics, both as objects of worship and for their many practical uses.

Ficus is a pan-tropical genus of trees, shrubs and vines occupying a wide variety of ecological niches; most are evergreen, but some deciduous species are endemic to areas outside of the tropics and to higher elevations.[2] Fig species are characterized by their unique inflorescence and distinctive pollination syndrome, which utilizes wasp species belonging to the Agaonidae family for pollination.

Some better known species that represent the diversity of the genus include the Common Fig which is a small temperate deciduous tree whose fingered fig leaf is well-known in art and iconography; the Weeping Fig (F. benjamina) a hemi-epiphyte with thin tough leaves on pendulous stalks adapted to its rain forest habitat; the rough-leaved sandpaper figs from Australia; the Creeping Fig (F. pumila), a vine whose small, hard leaves form a dense carpet of foliage over rocks or garden walls.

Read about Ficus in the Standard Cyclopedia of Horticulture

|

|---|

|

Ficus (ancient Latin name). Moraceae. The fig, the India rubber plant, the banyan tree and the creeping fig of conservatory walls belong to this vast and natural genus, which has over 600 species scattered through the warmer regions of the world. Ficus has no near ally of garden value. It is a genus of trees or shrubs, often climbers, with milky juice. In the common fig the lvs. are deeply lobed, but in most of the other species they are entire or else the margin is wavy or has a few teeth or an occasional small lobe. The lvs. are nearly always alternate, F. hispida being the only species of those described below which has opposite lvs. The foliage in Ficus varies from leathery to membranous, and is variable in venation, so the veins are very helpful in telling the species apart. Ficus is monoecious or rarely dioecious, the apetalous or sometimes naked minute fls. being borne inside a hollow more or less closed receptacle ; stamens 1—3, with short and united filaments ; pistillate fls. with 1- celled sessile ovary, ripening into an achene that is buried in the receptacle. What the horticulturist calls the fig, or fruit, is the fleshy receptacle, while the fruit of the botanist is the seed inside. In the following account, fruit is used instead of receptacle. The fertilization or caprification of the fig is one of the most interesting and complicated chapters in natural history, and is of great practical importance. The most important ornamental plant in the genus is the India rubber plant (F. elastica), which ranks amongst the most popular foliage plants for home use indoors. This is not the most important rubber-producing plant, both Hevea brasiliensis and Castilla elastica being producers of more and finer rubber. The creeping fig (F. pumila, better known as F. repens or F. stipulata) is one of the commonest and best climbers for covering conservatory walls. It clings close and makes a dense mat of foliage, which is about as dark in color as the English ivy. The plant has been cultivated since 1771, but within the last half-century has come to be recognized as the best plant for its special purpose. Once in a long while it fruits in conservatories, and the fruiting branches arc very unlike the barren ones. They stand out from the conservatory wall instead of lying flat and close. The leaves of the barren branches are less than an inch long and heart-shaped, with one side longer than the other at the base and a very short petiole; the leaves of fruiting branches are 2 to 3 inches long, elliptic-oblong, narrowed at the base, and with a petiole sometimes ½ inch long. Among the many wonders of the genus Ficus are the epiphytal habit of some, the huge spread of the banyan tree (F. benghalensis), and the fact that some species ripen their fruits under ground. Some of the tallest tropical trees are members of this genus, and often they begin life by climbing upon other trees. The ficus often overtops and outlives the other tree, which may be seen in every stage of decay, or may have entirely disappeared, leaving the giant climber twined spirally around a great hollow cylinder. The banyan tree sends down some of its branches (or aerial roots) into the soil, these take root, make new trunks, and eventually produce a great forest, in which it is impossible to tell the original trunk. The banyan in the botanic gardens at Calcutta sprang from a seed probably dropped by a passing bird into the crown of a date palm a little more than a century ago. The main trunk not many years ago, was 42 feet in circumference, with 232 additional trunks, many of them 8 to 10 feet in circumference, and the branches extend over an area 850 feet in circumference, forming a dense evergreen canopy through which sunlight never penetrates. The banyan under which Alexander camped, and which is said to have sheltered 7,000 men, now measures 2,000 ft. in circumference and has 3,000 trunks. Other species have the same method of propagation, but F. benghalensis is the most famous. The various species are cultivated both indoors northward and as shade and fruit trees in Florida and California. In this country the most important commercially is the fig, Ficus carica, now widely grown in California. The cultivation of Ficus elastica. The rubber plant (Ficus elastica) which is known all over this country, is perhaps the most popular and satisfactory house plant that has ever been cultivated. It Is a plant for the million. Some florists have several houses especially devoted to the propagation and cultivation of this tough and thrifty plant. There are several varieties of the rubber plant, but the true Ficus elastica is the best, both for growing and for selling. It can be easily told from the smaller-leaved variety, which is smaller and lighter colored in all its parts, the stem being smoother, and the sheath that covers the young leaves lacking the brown tint, which often runs into a bright Indian red. The method of propagating now popular in America employs old bushy stock-plants, either in pots or tubs, or planted out into a bed where the night temperature can be kept from 60° to 75° F. As soon as the young shoots are 5 to 6 inches long they are operated upon. An incision is made at the place where it is intended to root the young plant, cutting upward on a slant midway between two eyes, making the cut anywhere from 1 to 2 inches long, according to the thickness and length of the young shoot or branch. A small wedge, as a piece of match, is then inserted to keep the cut open. A large handful of clean, damp, well-prepared moss is then placed around the branch to cover the cut and is tied moderately firm with twine or raffia. Some use a small piece of charcoal for a wedge in the cut; others coat the two cuts with a mixture of charcoal dust and lime. The latter practice is beneficial in that it expedites the callusing of the cuts and the rooting of the young plant after being cut and mossed. The moss should be kept constantly moist, and the higher the temperature, within reasonable limits, the quicker the rooting process goes on. The roots of the young plant usually appear on the outside of the oval-shaped bunch of moss. A complete cut can then be made below the moss and the young plant potted. The smaller the pot at first the better. The leaves of the young plants should be tied up in order that they may not be injured by coming in contact with one another or by lying flat on the pots. The young plants now require a gentle bottom heat and frequent syringing,—a dozen times on clear days. As soon as the young plants are taken from the stock-plant, a little wax should be put on the end of the cut to prevent the milky sap from escaping. The best time of the year to propagate and root ficus is from the first of January to May.' The European growers never start much before the Christmas holidays; and ' from then until spring they make all their cuttings. The older method of propagating rubber plants is still the favorite one abroad; it employs single-eye cuttings. Sometimes, if the branches are very thick, only one-half the stem is taken with the eye and a single leaf, the leaf being curled up and tied with raffia, and the small piece with the eye set into the propagating-bed. This is a bed of sharp sand, or sometimes of sand and chopped sphagnum moss or fine cocoa-fiber. Frequently the single- eye cuttings are put at once into the smallest-sized thumb-pot,; with a mixture of very finely ground potsherd and charcoal filling about one- half the pot, and either soil or sand for the remainder. A small stick is used to hold the leaf upright. These pots are plunged into the propagating-benches in either sand, moss or fiber, and a steady bottom heat of 75° to 80° is applied and kept up until the plants are rooted. As a rule, such beds are inclosed in a glasshouse, in order to keep about them a close, warm and moist atmosphere. Only ventilation enough to permit the moisture caused by the evaporation to escape is allowed on these beds. In this country, propagation by the first described method can be continued nearly all the year round. From experience of both methods, the writer can say that the top-cutting and mossing process is better by far, especially where plenty of stock plants can be maintained. After being shifted from the smaller-sized pots into 3- or 4-inch pots, the young plants will stand a great deal of liquid manure as soon as they are rooted through or become somewhat pot-bound. Many propagators plant out the young plants from 3- and 4-inch pots into coldframes after the middle of May, or when all danger of night frost is past. They do very well in the bright, hot, open sun, but must receive plenty of water. After being planted out in frames, they should be potted not later than September, and for early marketing as early as August. The plan of planting out and potting in the later part of summer or early autumn is a very practicable one, as the plants do not suffer so much from the severe heat during the summer. CH

|

Cultivation

- Do you have cultivation info on this plant? Edit this section!

Propagation

- Do you have propagation info on this plant? Edit this section!

Pests and diseases

- Do you have pest and disease info on this plant? Edit this section!

Species

About 800, including:

- Ficus abutilifolia (Miq.) Miq. (= F. soldanella Warb.)

- Ficus adhatodifolia Schott

- Ficus aguaraguensis

- Ficus albert-smithii

- Ficus albipila — Abbey Tree, Phueng Tree, tandiran

- Ficus altissima

- Ficus amazonica

- Ficus americana

- Ficus andamanica

- Ficus angladei

- Ficus apollinaris Dugand (= F. petenensis Lundell)

- Ficus aripuanensis

- Ficus arpazusa[3]

- Ficus aspera

- Ficus aspera var. parcelli

- Ficus aurea — Florida Strangler Fig

- Ficus auriculataTemplate:Verify source — Roxburgh Fig

- Ficus barbata — Bearded Fig

- Ficus battieriTemplate:Verify source

- Ficus beddomei — Thavital

- Ficus benghalensis — Indian Banyan, Bengal Fig, East Indian Fig, borh (Pakistan), vad/vat/wad, nyagrodha, "indian fig"

- Ficus benjamina — Weeping Fig, Benjamin's Fig

- Ficus bibracteata

- Ficus bizanae

- Ficus blepharophylla

- Ficus bojeri

- Ficus broadwayi

- Ficus bubu Warb.

- Ficus burtt-davyi Hutch.

- Ficus calyptroceras

- Ficus capreifolia Del.

- Ficus carchiana C.C.Berg

- Ficus carica — Common Fig, anjeer (Iran, Pakistan), dumur (Bengali)

- Ficus castellviana

- Ficus catappifolia

- Ficus citrifolia — Short-leaved Fig, Wild Banyantree

- Ficus clusiifoliaTemplate:Verify source

- Ficus congesta

- Ficus cordata Thunb.

- Ficus cordata ssp. salicifolia (Vahl) Berg

- Ficus coronata — Creek Sandpaper Fig

- Ficus costaricana (Liebm.) Miq.

- Ficus cotinifolia

- Ficus crassipes — Round-leaved Banana Fig

- Ficus crassiuscula Standl.

- Ficus craterostoma Warb. ex Mildbr. & Burr.

- Ficus cristobalensis

- Ficus cyclophylla

- Ficus dammaropsis — Highland Breadfruit, kapiak (Tok Pisin)

- Ficus dendrocida

- Ficus deltoidea — Mistletoe Fig

- Ficus destruens

- Ficus drupacea

- Ficus ecuadorensis C.C.Berg

- Ficus elastica — Indian Rubber Plant, Rubber Fig, "rubber tree", "rubber plant"

- Ficus elastica cv. 'Decora'

- Ficus elastica var. variegata

- Ficus elasticoidesTemplate:Verify source

- Ficus elliotianaTemplate:Verify source

- Ficus enormisTemplate:Verify source

- Ficus erecta — Japanese fig, イヌビワ

- Ficus faulkneriana

- Ficus fischeri Warb. ex Mildbr. & Burr. (= F. kiloneura Hornby)

- Ficus fistulosa

- Ficus fraseri — Shiny Sandpaper Fig, White Sandpaper Fig, "figwood", "watery fig"

- Ficus fulvo-pilosa Summerh.

- Ficus gardnerianaTemplate:Verify source

- Ficus gibbosa

- Ficus gigantosyce Dugand

- Ficus gilletiiTemplate:Verify source

- Ficus glabraTemplate:Verify source

- Ficus glaberrima

- Ficus glumosa (Miq.) Del. (=F. sonderi Miq.)

- Ficus godeffroyi (endemic to Samoa, known as Mati.)

- Ficus gomelleiraTemplate:Verify source

- Ficus greenwoodii Summerh.

- Ficus greiffiana

- Ficus grenadensis

- Ficus grossularioides — White-leaved Fig

- Ficus guajavoides Lundell

- Ficus guaranitica[4]

- Ficus guianensis[5]

- Ficus hartii

- Ficus hebetifolia

- Ficus hederacea

- Ficus heterophylla

- Ficus hirsuta

- Ficus hirta Vahl

- Ficus hispida

- Ficus hispita L.

- Ficus ilicina (Sond.) Miq.

- Ficus illiberalis

- Ficus insipida

- Ficus insipida ssp. insipida

- Ficus insipida ssp. scabra

- Ficus kerkhovenii — Johore Fig [6]

- Ficus luschnathiana (Miq.) Miq.

- Ficus infectoria — Wavy-leaved Fig, plaksa

- Ficus ingens (Miq.) Miq.

- Ficus krukovii

- Ficus lacor

- Ficus lacunata

- Ficus laevigata

- Ficus laevis

- Ficus lapathifolia

- Ficus lateriflora

- Ficus lauretana

- Ficus loxensis C.C.Berg

- Ficus lutea Vahl (= F. vogelii, F. nekbudu, F. quibeba Welw. ex Fical.)

- Ficus lyrata — Fiddle-leaved Fig

- Ficus macbrideiTemplate:Verify source Standl.

- Ficus maclellandii — Alii Fig or Banana-Leaf Fig

- Ficus macrocarpaTemplate:Verify source

- Ficus macrophylla — Moreton Bay Fig

- Ficus magnifolia

- Ficus malacocarpa

- Ficus mariaeTemplate:Verify source

- Ficus masonii Horne ex Baker

- Ficus mathewsii

- Ficus matiziana

- Ficus mauritiana

- Ficus maxima

- Ficus maximoides C.C.Berg

- Ficus meizonochlamys

- Ficus mexiae

- Ficus microcarpa — Chinese Banyan, Malayan Banyan, Curtain Fig, "Indian laurel"

- Ficus microcarpa var. hillii — Hill's Fig

- Ficus microcarpa var. nitida — often considered a subspecies of F. retusa or a distinct species

- Ficus microchlamys

- Ficus minahasae — longusei (SulawesiTemplate:Verify source)

- Ficus mollior F.Muell. ex Benth.

- Ficus monckii

- Ficus montana — Oakleaf Fig

- Ficus muelleri

- Ficus muelleriana

- Ficus mutabilis

- Ficus mutisii Dugand

- Ficus mysorensis

- Ficus natalensis Hochst. — mutuba (Luganda)

- Ficus natalensis ssp. leprieurii

- Ficus natalensis ssp. natalensis

- Ficus neriifolia

- Ficus nervosa

- Ficus noronhae

- Ficus nota — tibig

- Ficus nymphaeifoliaTemplate:Verify source

- Ficus oapana C.C.Berg

- Ficus obliqua — Small-leaved Fig

- Ficus obtusifolia

- Ficus obtusiuscula (Miq.) Miq.

- Ficus opposita — Sweet Sandpaper Fig, Sweet Fig, "figwood", "watery fig"

- Ficus organensis (Miq.) Miq.

- Ficus padifolia

- Ficus pakkensis

- Ficus pallida

- Ficus palmata

- Ficus pandurata

- Ficus pantoniana — Climbing Fig

- Ficus panurensis

- Ficus pertusa

- Ficus petiolaris (= F. palmeri)

- Ficus pilosa

- Ficus piresiana Vázq.Avila & C.C.Berg

- Ficus platypoda — Desert Fig, Rock Fig

- Ficus pleurocarpa — Banana Fig, Gabi Fig, Karpe Fig

- Ficus polita Vahl

- Ficus polita ssp. polita

- Ficus prolixa G.Forst. (= F. mariannensis Merr.)

- Ficus pseudopalma Blanco

- Ficus pulchella

- Ficus pumila — Creeping Fig

- Ficus pyriformis

- Ficus racemosa — Cluster Fig, Goolar Fig, udumbara (Sanskrit), umbar (India)

- Ficus ramiflora

- Ficus religiosa — Sacred Fig, arali, bo, pipal, pippala, pimpal (etc.), pou (Cambodia), Ashvastha

- Ficus retusa — Taiwan Fig, Ginseng Fig, "Indian laurel", "Cuban-laurel"

- Ficus rieberiana C.C.Berg

- Ficus roraimensis

- Ficus roxburghiiTemplate:Verify source

- Ficus rubiginosa — Port Jackson Fig, Little-leaved Fig, Rusty Fig, damun (Sydney Language)

- Ficus rumphii Blume — Rumpf's Fig

- Ficus salicifolia Vahl (= F. pretoriae Burtt Davy) — Willow-leaved Fig

- Ficus salzmanniana

- Ficus sansibarica Warb.

- Ficus sarmentosaTemplate:Verify source

- Ficus saussureana

- Ficus scabra G.Forst.

- Ficus schippii

- Ficus schultesii

- Ficus schumacheri

- Ficus septica Burm. F. var. septica Moraceae — Hauli Tree in Philippines

- Ficus sphenophylla

- Ficus stahlii

- Ficus stuhlmannii Warb.

- Ficus subpuberula

- Ficus superba

- Ficus superba var. henneana

- Ficus sur Forssk. (= F. capensis)

- Ficus sycomorus — Sycamore Fig, Fig-mulberry

- Ficus sycomorus ssp. sycomorus

- Ficus sycomorus ssp. gnaphalocarpa (Miq.) C.C. Berg

- Ficus tettensis Hutch. (= F. smutsii Verdoorn)

- Ficus thonningii

- Ficus tinctoria — Dye Fig, Humped Fig

- Ficus tobagensis

- Ficus tomentellaTemplate:Verify source

- Ficus tomentosa

- Ficus tonduzii Standl.

- Ficus tremula Warb.

- Ficus tremula ssp. tremula

- Ficus triangularis

- Ficus trichopoda Bak. (= F. hippopotami Gerstn.)

- Ficus trigona L.f.

- Ficus trigonata

- Ficus triradiata — Red-stipule Fig

- Ficus ulmifolia

- Ficus umbellataTemplate:Verify source

- Ficus ursina

- Ficus variegata Bl.

- Ficus variegata var. chlorocarpa King

- Ficus variolosa

- Ficus velutina

- Ficus verruculosa Warb.

- Ficus virens — White Fig, pilkhan, an-borndi (Gun-djeihmi)

- Ficus virens var. sublanceolata White Fig, New South Wales

- Ficus virgata

- Ficus wassa

- Ficus watkinsiana — Watkins' Fig, Nipple Fig, Green-leaved Moreton Bay Fig

- Ficus yoponensis Desv.

Read about Ficus in the Standard Cyclopedia of Horticulture

|

|---|

|

{{{1}}} The above text is from the Standard Cyclopedia of Horticulture. It may be out of date, but still contains valuable and interesting information which can be incorporated into the remainder of the article. Click on "Collapse" in the header to hide this text. |

Gallery

If you have a photo of this plant, please upload it! Plus, there may be other photos available for you to add.

Figs of a variegated Ficus aspera

Giant Ficus obliqua.

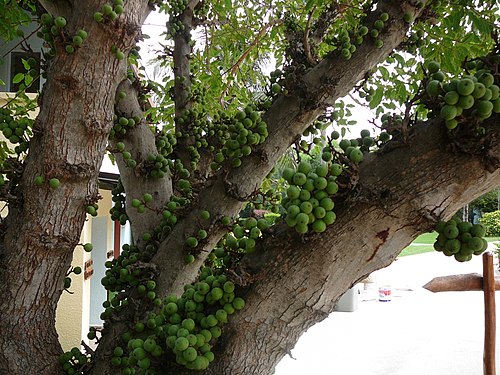

Fruits on the trunk of a Ficus in India

References

- Standard Cyclopedia of Horticulture, by L. H. Bailey, MacMillan Co., 1963

External links

- w:Ficus. Some of the material on this page may be from Wikipedia, under the Creative Commons license.

- Ficus QR Code (Size 50, 100, 200, 500)

- ↑ Sunset Western Garden Book, 1995:606–607

- ↑ Handbook of Flowering Volume 6 of CRC Handbook of Flowering ISBN 9780849339165

- ↑ Brazil. Described by Carauta & Diaz (2002): pp.38–39

- ↑ Brazil, Paraguay and Argentina: Carauta & Diaz (2002): pp.64–66

- ↑ Brazil: Carauta & Diaz (2002): pp.67–69

- ↑ Changitrees